Often times, when I'm supposed to be doing something more important, I'll sneak away into my maps and notes on the world of the Merry Mariner. I might tweak the culture of this city or fiddle with the history that region, or I might just zoom way in and imagine myself on the ship's deck, ringing the bell and sailing into some bustling harbor or cruising past high, forbidding cliffside villages or drifting through murky brown waters in a dark and feral jungle. Wandering around in the vast world I'm creating is one of my favorite things about working on this project. In a way, writing the stories is just an excuse to do exactly that!

But world-building isn't all daydreaming. A convincing, airtight universe is crucial to storytelling, particularly fantasy, where so much depends on exploration and wonder. As I see it, building up the world of the Seven Seas has two main purposes. First, it ensures that each story feels a part of a larger whole. The characters refer to places, objects, people and historical events beyond the pages of the current story, but which you might encounter first-hand in another tale; it makes for an intricate background tapestry from which details may be plucked at any point to enrich and deepen the reader's journey. Mamma doesn't just use sausages in her stew, for example, she uses sausages from the White Woods, a place that exists in this world, to which you can point on a map, and where you might very well find yourself in the next story.

But world-building isn't all daydreaming. A convincing, airtight universe is crucial to storytelling, particularly fantasy, where so much depends on exploration and wonder. As I see it, building up the world of the Seven Seas has two main purposes. First, it ensures that each story feels a part of a larger whole. The characters refer to places, objects, people and historical events beyond the pages of the current story, but which you might encounter first-hand in another tale; it makes for an intricate background tapestry from which details may be plucked at any point to enrich and deepen the reader's journey. Mamma doesn't just use sausages in her stew, for example, she uses sausages from the White Woods, a place that exists in this world, to which you can point on a map, and where you might very well find yourself in the next story.

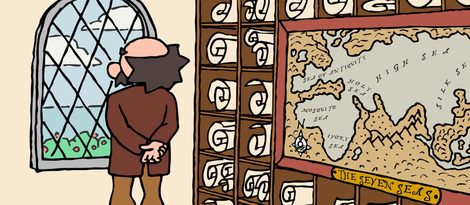

The second purpose of world-building is to create wonder and mystery--not for the reader, necessarily, but for myself. The driving force of the Merry Mariner series is the joy of exploration and discovery. That means I have to create a world that just begs to be explored and discovered. I need a map that, when I look at it, I'm dying to see up close and personal. That burning desire to visit these new and fantastical places fuels the stories, chiefly through Verona, who is a personification of this emotion of mine. If successful, that feeling will soak into the words on the page and into the minds and hearts of the readers.

So how do I do it?

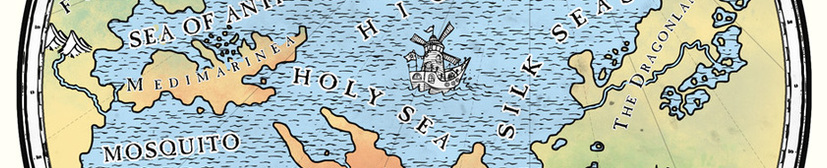

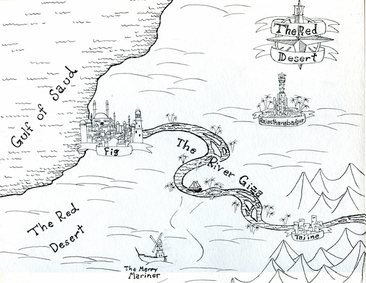

Here is a map which resembles the map on the World page, but which you'll notice is visually more simple and at the same time labeled in much more detail. This is my personal master map.

So how do I do it?

Here is a map which resembles the map on the World page, but which you'll notice is visually more simple and at the same time labeled in much more detail. This is my personal master map.

I'm not going to let you look closer at it because it's riddled with such names as [Amazonian-ish River Tribes Here] and [Everest-esque Mountain Here]. It's not meant to ever be seen by the reader. It's my god's-eye-view of the Seven Seas, my sandbox where I can create or destroy entire civilizations with a single click, and as any work in progress, it's full of [Insert City Here].

You've probably noticed that the world of the Seven Seas is simply the continents of Europe, Africa, and Asia, with water and land mass inverted. None of those names, however, appear on the map. That's because the idea is that Merry Mariner stories walk a fine line between reality and fantasy, not falling completely into either camp. The world should feel familiar but distant, like a child's daydream in geography class or a naive nostalgic memory from youth. The reader should know precisely where they are and simultaneously have no idea what could appear around the bend. The inverted map serves this purpose perfectly--familiar, yet wholly strange.

The names of people and places must follow this convention, reminding readers of a specific place and culture, yet unspecific enough to feel fantastical. This is harder than you might think, not least because I am only one perspective on the world, and what sounds exotic and interesting to me will undoubtedly feel contrived to someone else.

So we have names such as the Silk Seas (to remind one of the ancient Silk Road), the Monsoon River (bringing to mind torrential downpours in the jungle), and Medimarinea ("Mediterranean Sea" derives from the Latin words medius and terra, meaning "in the middle of the land," so the logical inversion is simply medius + mare, or "in the middle of the sea"). Sometimes I'll name places after objects known to derive from that area of the world (Ivory Sea), or mythological commonalities between cultures in the area (The Dragonlands). I try to avoid cliché as much as possible ("Jade Sea"? Really, George R. R. Martin?), and I especially try to avoid just making up nonsense. There's not much worse than opening a fantasy book set in the Land of Boffle, where the Good Folk of Quimbly are under siege by the cruel Flarps from Porlax. How is anyone supposed to relate to that?

You've probably noticed that the world of the Seven Seas is simply the continents of Europe, Africa, and Asia, with water and land mass inverted. None of those names, however, appear on the map. That's because the idea is that Merry Mariner stories walk a fine line between reality and fantasy, not falling completely into either camp. The world should feel familiar but distant, like a child's daydream in geography class or a naive nostalgic memory from youth. The reader should know precisely where they are and simultaneously have no idea what could appear around the bend. The inverted map serves this purpose perfectly--familiar, yet wholly strange.

The names of people and places must follow this convention, reminding readers of a specific place and culture, yet unspecific enough to feel fantastical. This is harder than you might think, not least because I am only one perspective on the world, and what sounds exotic and interesting to me will undoubtedly feel contrived to someone else.

So we have names such as the Silk Seas (to remind one of the ancient Silk Road), the Monsoon River (bringing to mind torrential downpours in the jungle), and Medimarinea ("Mediterranean Sea" derives from the Latin words medius and terra, meaning "in the middle of the land," so the logical inversion is simply medius + mare, or "in the middle of the sea"). Sometimes I'll name places after objects known to derive from that area of the world (Ivory Sea), or mythological commonalities between cultures in the area (The Dragonlands). I try to avoid cliché as much as possible ("Jade Sea"? Really, George R. R. Martin?), and I especially try to avoid just making up nonsense. There's not much worse than opening a fantasy book set in the Land of Boffle, where the Good Folk of Quimbly are under siege by the cruel Flarps from Porlax. How is anyone supposed to relate to that?

From the very beginning, the idea with the Merry Mariner books was to set each one in a different climate environment. The first book, The Merry Mariner Sails the Sands, will clearly be set in the desert. Then there will be books in the bog/swamp, snow/ice, sky, jungle, and, of course, the open sea. Each of the main regions on the map represents one of these biomes: the Red Desert (desert), the Foglands (bog), Arctica (snow), the Dragonlands (sky), and the Monsoon River (jungle), corresponding very roughly to the Middle East, northern Europe, the North and South Poles, East Asia, and Southeast Asia/the Amazon, respectively. Then there are the other regions in between which won't necessarily feature in their own book, but which are important to fill out the world - Medimarinea (the Mediterranean, as mentioned), the Ramayana Mountains (the Himalayas), and Monda Nova (the Americas), the latter two of which haven't yet been added to the world map (I'm not sure I like "Monda Nova." It's a bit on the nose). These places will be mentioned, or perhaps visited in a short story.

I've recently fleshed out each region with its own capital city, other major and minor cities, geographical features, and a bit about the culture, leadership, and products which the people of the regions and provinces produce. By blurring real-life cultures together, mixing them up and swapping features between them, I hope to achieve that balance of fantasy and reality, of familiar and strange.

In early drafts of The Merry Mariner Sails the Sands, for example, the capital of the Red Desert region was Fig, a swirling sandy mix of Istanbul, Cairo, Baghdad, and Marrakech. The name came from the fruit, native to the Middle East, and from Figuig, a lovely little oasis-town on Morocco's border with Algeria. I recently decided I don't like it, however. It's too North Africa and not enough Arabia; it's too simple and understated for such a mighty and important city. It needed a new name, one which would capture the Arabic grandeur without being too specific to any one culture.

In early drafts of The Merry Mariner Sails the Sands, for example, the capital of the Red Desert region was Fig, a swirling sandy mix of Istanbul, Cairo, Baghdad, and Marrakech. The name came from the fruit, native to the Middle East, and from Figuig, a lovely little oasis-town on Morocco's border with Algeria. I recently decided I don't like it, however. It's too North Africa and not enough Arabia; it's too simple and understated for such a mighty and important city. It needed a new name, one which would capture the Arabic grandeur without being too specific to any one culture.

After much hemming and hawing, I finally settled on "Ishtar." She was the ancient Egyptian goddess of fertility, love, and war, but the name is most well-known from the Ishtar Gate, eighth gate of the ancient city of Babylon, which has been brilliantly reconstructed in Berlin. Also, there was a 1987 film by that name featuring Dustin Hoffman and Warren Beatty wandering around Morocco. The word "Ishtar" is just sort of floating around in the public subconscious as vaguely associated with the Middle East and the Sahara Desert, and that makes it the perfect name.

Less ideal is the name I'd come up with for the capital of the Foglands, which must be the seat of the Queen and a mix of turn-of-the-century Paris, London, and other big European cities. Despite their proximity, there's actually very little that Paris and London have in common, culturally speaking. So I tried combining the names (Londris? Pardon? Lonpardonis?), I tried using the English Channel (which the French call La Manche - Manchel? Chanche?), and I searched desperately for something historical in common (Norman? Bretanis? Franglo?), all in vain. What I currently have is "Ville." It's short, vaguely French but also used somewhat in English. What I don't like is that it sounds like a small town, when it should sound like a bustling metropolis. We'll see what I can do about it.

So that's a bit about world-building! Happy travels...

- M. Ray

Less ideal is the name I'd come up with for the capital of the Foglands, which must be the seat of the Queen and a mix of turn-of-the-century Paris, London, and other big European cities. Despite their proximity, there's actually very little that Paris and London have in common, culturally speaking. So I tried combining the names (Londris? Pardon? Lonpardonis?), I tried using the English Channel (which the French call La Manche - Manchel? Chanche?), and I searched desperately for something historical in common (Norman? Bretanis? Franglo?), all in vain. What I currently have is "Ville." It's short, vaguely French but also used somewhat in English. What I don't like is that it sounds like a small town, when it should sound like a bustling metropolis. We'll see what I can do about it.

So that's a bit about world-building! Happy travels...

- M. Ray

RSS Feed

RSS Feed